Bradford Observer Thursday, May 14, 1857

DREADFUL MURDER AND SUICIDE AT LIDGET GREEN

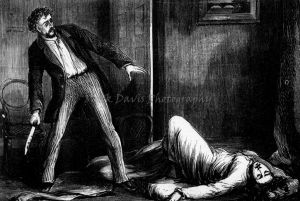

The quiet and rural locality of Lidget Green was at midnight on Monday the scene of a dreadful murder, which was quickly followed by the deliberate suicide of the murderer. The murderer was Samuel Charlton, 68 years of age, and his victim was Hannah Holroyd, aged 42. They were persons in a humble condition. Charlton was an assistant to bailiffs, and a person of very indifferent character. He was a widower, and had five or six children, all of them being able to maintain themselves. Hannah Holroyd was a widow, and had five children, the youngest of which was under five years of age.

They both resided in the same street – Club street – at Lidget Green; the cottage of one being nearly opposite that of the other.

Since Whitsuntide last, an intimacy partaking of the character of courtship has sustained between Charlton and Mrs. Holroyd, the former going regularly to the house of the latter, and being frequently seen with her abroad in the neighbourhood, as well as in Bradford. Some differences had, however, latterly arisen between them, on account of Mrs Holroyd favouring the advances of a rival suitor who appeared a much younger man, Luke Normington, aged 30, just returned from serving in the militia. The circumstances exceedingly troubled Charlton, and he had often been heard to declare, with great bitterness, that if she persisted in showing this preference for his rival, he would take away her life, and then destroy his own. It was this feeling of jealousy that at length drove the wretched man to commit the horrible crimes that he had thus contemplated.

On Monday evening he accompanied Mrs. Holroyd to a temperance meeting at Lidget Green, for he had practised total abstinence for some time past. As they returned, his rival, Luke Normington, encountered Mrs. Holroyd, and spoke to her, but she passed forward, shortly calling at the house for a neighbour, not far from her own dwelling. Charlton proceeded to her house, and there awaited her arrival, silent and sullenly. She returned soon after eleven o’clock, but she again spoke with Normington on her way to her own house. Both Charlton and Mrs. Holroyd were left sitting before the fire when the eldest daughter retired to rest in the chamber, about half-past eleven. Nothing had then been said by either of them, and quietness continued. What occurred afterwards, before the tragic deed was perpetrated, there is none to tell. Soon after half-past twelve, the eldest daughter of Mrs. Holroyd was awakened by hearing the house door close. She then heard the door open, and the departing footsteps of Charlton. The light was burning in the house, and the circumstances led the daughter to suppose that her mother, who slept on the ground floor, had fallen asleep and left the candle burning. She immediately went down stairs for the purpose of locking the door and putting out the light. She bolted the door, and on turning round hence to her horror, she discovered the body of her mother lying weltering in blood, on the opposite side of the room. She was undressed as if she was prepared to retire to rest, and had her boots on.

The piercing shrieks of the distressed young woman quickly brought several persons to her assistance. Policeman Binns was in the immediate neighbourhood, and on going to the door found it locked outside, the key remaining in the door. On entering, he found Mrs. Holroyd quite dead. Her head had been nearly severed from her body, and her right hand was slightly cut. Ascertaining that Charlton had been recently in the house, he crossed the road to inquire for him at his house. He then learnt from his daughter that he had entered about ten minutes or a quarter of an hour before, that he shook hands with his children, and, saying, “Farewell, you will never see me again,” then hurriedly departed. On leaving, she heard him return for a moment and lift up the cellar grate, and then go on his way. On going into the cellar, Binns found a razor which was covered with blood. Several officers, Sergeant Knowles, P. C. Binns, and Constable Jowett, immediately proceeded to search the neighbourhood for the murderer; and by this time a large number of persons were attracted to the place by the report of the horrible tragedy. They soon came to the conclusion that Charlton would destroy himself by drowning, and this belief gained strength as time wore on.

The officers and their assistants consequently not only searched the fields in the immediate neighbourhood, but the mill dams and the streams. At four o’clock on Tuesday morning, the body of Charlton was found drowned in New Miller’s Dam. His hat was floating on the upper part of the dam. The body was shortly afterwards discovered at some distance from the embankment below. It was floating in a perpendicular position, just beneath the water. It was untimely recovered and removed to the new Miller’s Dam public-house.

We need hardly say that this tragedy has created the greatest sensation in the district, and especially in the immediate locality of the scene.

THE INQUESTS

The inquest on Hannah Holroyd was held yesterday afternoon, at the Second West Inn, Lidget Green, before Mr. George Dyson, coroner, and the following jury: – Mr. Edwin Bentley, foreman; Mr. Francis Ackroyd, Mr. Alexander Wild, Mr. Joshua Horsfall, Mr. John Hudson, Mr. Jonas Jennings, Mr. Aaron Topham, Mr. Benjamin Crabtree, Mr. Wm Wardle, Mr. Charles Fox, Mr. Henry Suddards, Mr. Walton, and Mr. Jeremiah Rudd.

Martha Holroyd, ‘the daughter of the deceased was the first witness called. She said- I am 19 years of age. I work at Mr. John Turner’s mill. I am daughter of Hannah Holroyd, the deceased. My father, Joshua Holroyd, die about five years ago. He was a quarryman. There are five children-the youngest is about four years of age. I knew Samuel Charlton. He had no trade; he was a sort of bailiff. I don’t know if he intended to marry my mother; but he has been in the habit of coming in and sitting in our house. He has not been well received for some time past; she did not take him in properly. He had never threatened to do her injury in my hearing. I saw him on Monday evening about seven o’clock. My mother went to a teetotal meeting at Lidget Green. She came home from the meeting about half past eleven, having called at a neighbour’s house. Charlton came straight from the meeting. He was in the house an hour before she came in. He never spoke during the time he was there. When she came in, I went upstairs to bed. I left my mother sitting on a chair in front of the fire, and he was sitting at the side of the fire. My mother was cheerful when I went to bed, but Charlton neither laughed nor spoke. It would be about twenty minutes to twelve when I went to sleep. There had been no quarrel then. I never heard them speak at all. When I awoke, about a quarter to one, I saw a light which shone up stairs, I having left the door open. I heard the house door open, and I heard by his (Charlton’s) step that he came to the door and went back again. He went immediately. I heard the door shut, but I did not hear him lock it. I thought my mother might have fallen asleep, and I went down to fasten the door, which I feared she might have forgotten to lock. I heard neither scream nor scuffle. I barred the door, and then found my mother lying in blood upon the floor, with her feet towards the fire place. I then found the door locked outside. I gave an alarm. Abraham Pearson, Henry Jowett, constable, and Binns, policeman, came in. I know Luke Normington. My mother rather leaned to Luke. He met her as she was coming from a neighbouring house, on Monday night, and “clicked” hold of her. I went for her and saw him stop her. Charlton was at that time at her house. My mother was nearly undressed at the time she was found. I don’t know that Charlton ever stopped all night. Luke Normington had been two or three times at our house, but he did not come at the time I gave an alarm.

Policeman Binns was next called. He swore: – At a quarter before one on Tuesday morning, i was on duty at Lidget Green. I was standing twenty yards from the place, when I heard a cry of “Murder.” I went to the place and found the door locked. On being admitted, I found the deceased lying on the floor with her throat cut. She was nearly undressed; she had only her chemise, her night gown, and boots on. I asked who had been in last, and was told Samuel Charlton. I then went to his house opposite in the street, and I inquired of his daughter whether her father was in. She stated that he had been there about a quarter of an hour before, had bid them all good bye, and then gone away. She also said that he had lifted up the grate and thrown something down. On going down into the cellar, I found the razor which is now produced, and which I gave to Constable Jowett. It was covered with blood, and is now stained with blood. Sergeant Knowles and I sought Charlton in the neighbourhood, and about four o’clock found the body in New Miller’s dam. I have known Charlton for several years. He did not bear the best of characters. I have seen Luke Normington go in and out of the house several times, and when I heard the scream on Tuesday night, I saw Luke Normington run away and he said, that he was afraid if he were seen he would be blamed. Luke came from this inn, about twenty minutes to one o’clock, and the screech occurred about five minutes after. I followed him from this house to the other. The screech occurred, and he ran away.

Ellen Dyson, daughter of Samuel Charlton, lived with us. He left the house about eight o’clock at night. He was going to the teetotal meeting. I know he kept company with the deceased. He returned home about one o’clock by our clock, which is twenty minutes too soon. He came to the bedside and bade us all farewell; he said we should never see him again. He appeared in great trouble. He then bade us good night, and went out. I heard him immediately come up the door stones, and lift up the grate. I know nothing of any razor: I saw one which Binns afterwards got from the cellar. We had never had anything wrong; we thought nothing of what he had said. My father had never said he would do her harm. He had kept company with her since Whitsuntide.

David Naylor, landlord of the Second West Inn, was called. He said: I know Luke Normington. He was in my house nearly all the evening, from something like six o’clock till one, but going out occasionally. He was in this house from twelve till ten minutes to one. He went about half-past ten, and came in about half-past eleven o’clock. He then stopped till ten minutes to one. He was rather “fresh” when he went out.

The Coroner then directed the jury’s attention to the facts adduced in the evidence. He could not suggest any doubt in the matter. It was one which was very simple and clear, and quite sufficient to send a person for trial and to hang him. Charlton was left sitting with the woman about a quarter to twelve, and in about an hour afterwards she was found weltering in blood, with her throat cut. He was found to have left the house about the same time, to go to his own house, and to take leave of his family. There was no doubt that if Charlton had been living, he would have been sent for trial. The jury immediately returned a verdict of “Wilful Murder against Samuel Charlton.”

An inquest was afterwards held on Samuel Charlton, by Mr. Dyson and the following jury, at the New Miller Dam Inn:- Mr. John Fearnsides, foreman; Messrs. James Reaney, S. Settle, J. Denby, R.Collins, T. Bastow, Reuben Askwith, J. Willman, J. Clark, T. Pitt, E. Anderton, and James Halliwell.

The Coroner read the evidence which had been taken at the former inquest, telling the jury that a verdict of “Wilful Murder” had been returned against Samuel Charlton, and that it was for them to determine whether the deceased Samuel Charlton had fallen by accident into the dam or whether he had died from felo de se.

John Knowles, sergeant in the Bradford police force, was first called. He deposed: I was on duty at Lidget Green on Monday night. I went to visit Reuben Binns on his beat at Lidget Green, at one o’clock. When I was in Legrams Lane, I heard his signal-a double whistle-and I went back to him. I was between two and three hundred yards from his him. He said there had been a murder on the Green. I went to the house of Hannah Holroyd. The woman was lying weltering in blood, on the floor, with her throat cut, quite dead. I made enquiries as to who had been in the house, and the daughter said she had left Charlton sat by the fire. I made a search for the weapon, but could find none. I then went to Ellen Dyson’s to look for him, but did not find him. The daughter said that Charlton had been in some twenty minutes before, and had gone away. I then went to Great Horton and called the surgeon, Mr. Thomas. I got a lamp and made a search through the fields on Scholemoor and Birks. I was then joined by Superintendent Burniston of the Bradford police force. I then went back to Lidget Green and heard that the razor was found. I came down Thief score Lane and searched all the becks to the New Miller Dam. Coming on the south side I found a hat floating near the top. I then went 100 to 150 yards along the dam side, and I saw something floating in the water which I found to be the skirts of his coat. On examination, I found the body of the deceased. He was four or five yards from the side. He was floating-his feet did not touch the bottom. I then called up the people at the boat house, and he was conveyed to the New Miller Dam Inn. He appeared quite fresh, as if he had not been long in the water. His clothes were correct, and there was no mark of injury upon him. I have known him for a long time. I had him once in custody for felony, and recently he has been committed for a month under the Worsted Act. His general character was not good. He dealt in cotton and worsted waste. I have seen him repeatedly with Hannah Holroyd since last Whitsuntide. I have known him to be in her house all night for several nights in the week. He was of perfectly sound mind. I saw him last Saturday night.

Mr. Jonas Denby (one of the jury) said that he let the house to Charlton, for Mrs. Holroyd, about seven months ago, and he had frequently seen them together as man and wife. She always paid the rent.

Henry Jowett, a constable at Great Horton, said: I received information of this occurrence about a quarter past one. Sergeant Knowles called me up. On going to the woman’s house we found her laid in her own blood, and the floor covered with blood. Her throat was cut, as well as one of her fingers on the right hand, and she was quite dead. I was told of Charlton having been with her. His daughter said that he had gone out about an hour since, and bid them all goodbye. She said he had opened the grating and dropped something in. I was with P.C. Binns when he found the razor produced in the cellar. There is blood upon it. It was put under the cellar plate. I went in search towards the old dam at Lidget Green, over the fields, in the direction of Great Horton. I have known Charlton for 30 years. He was a man of bad character, and I believe he was a man of sound mind.

The Coroner then briefly directed the attention of the jury to the nature of the evidence, and asked them to consider whether from that evidence the deceased was of sound mind or not, because, if they were of opinion that he was in a sound mind, their verdict would be felo de se.

The Jury then deliberated for a brief period, and returned a verdict of felo de se.

The Coroner said that he would have to give to the constable a warrant ordering the body to be interred between the hours of nine and twelve the same night. During twenty years, this was the first instance of felo de se which had occurred in more than 3000 inquests, in his district.

Bradford Observer, Thursday May 21, 1857

A MIDNIGHT FUNERAL OF A MURDERER

At the close of the inquest on Samuel Charlton, on Wednesday evening, the constable, in obedience to the coroner’s warrant, proceeded to make arrangements for the interment of the body of the deceased, the act of parliament requiring that a “felo de se” shall be interred within 24 hours after the inquest, and between the hours of nine and twelve o’clock at night. Accordingly a grave was ordered to be dug in the burial ground attached to the Primitive Methodist Chapel, at Great Horton. The reason for the selection of this burial ground was that the wife and other relatives of the deceased had been interred in that place. About eleven o’clock the same night, the body conveyed to Great Horton, under the direction of the relieving officer of the district. A crowd of more than 2,000 persons had assembled on the road in front of the chapel yard, and great confusion prevailed. The mob were loud in expressing their objection to the interment of the corpse. The authorities of the chapel were opposed to its interment, and they had many sympathisers in the crowd.

They met the bearers of the coffin at the gates on its being taken from the hearse, and endeavoured to prevent its entrance into the ground. The uproar and disturbance were very unseemly, and exclamations, such as “Throw it over the wall,” “Burn it,” &c., were mingled in the uproar. By the aid of the police the coffin was at last got to the grave side; but then objection was taken to the grave not being deep enough, and also to its being an old one. The consequence was that the sextons proceeded to dig a new grave in a plot of virgin soil adjoining. Meanwhile the uproar and confusion prevailed for many hours. Some person addressed the crowd, dilating on the vicious character of the deceased, and expressing regret that the annuals of Horton should be darkened with the record of a foul murder. The new grave having been dug, the interment was at length completed, without the usual rites. Many of the crowd remained on the spot till five o’clock on Thursday morning.

THE BRADFORD OBSERVER May 21, 1857

THE MURDER AND SUICIDE AT LIDGET GREEN

To the Editor of the Bradford Observer

Sir, – In justice to teetotalism, and as secretary to the Great Horton Temperance Society, I feel it my duty to correct a statement which appears in your paper of Thursday last, with respect to Charlton having “accompanied Mrs Holroyd to a temperance meeting at Lidget Green, for he had practised total abstinence for some time past.”

In the first place, I may state that she was not accompanied by Charlton, but came in at a different period and sat at the opposite end of the room during the whole of the meeting. In the next place, I beg to observe that he had not practised total abstinence for some time past. It is true that in July he signed the pledge, but which I regret to say he only kept about a month.

From that time up to the time of the murder he frequently indulged in intoxicating drinks.

By giving insertion to the above you will greatly oblige,

Sir, your obedient servant,

JOSEPH WILSON.

11, Ebenezer Place, Great Horton, May 18th, 1857

THE BRADFORD OBSERVER Thursday October 25, 1860

During the week our own town has been the scene of an appalling tragedy. A mother, driven to desperation by the heartless conduct of her reputed husband, destroyed her two infant children, and attempted to take her own life. In the last attempt she failed, and on a discovery of the circumstance being made, she was removed to the Infirmary, where she now lies in a precarious state. The facts as brought out at the inquest will be found narrated in another column; we have her only to express our deep regret that the criminal annals of Bradford, for the most part so free from serious offences, should be burdened with a crime of such an appalling and, in its accessories, of such a revolting character. We need not say that the poor woman is the object of general commiseration.

DREADFUL TRAGEDY

MURDER OF TWO CHILDREN AND ATTEMPTED SUICIDE

Our quiet and orderly community has this week been thrown into great and unusual excitement by a tragedy unparalleled in atrocity in this district. Bradford, with its dense population, has happily been comparatively free from those fearful crimes against life which have characterised many large communities, and the occurrence of such a dreadful outrage now has excited feelings of intense horror and melancholy.

The murder in this instance is a double one, and the victims are the innocent offspring of a ‘poor, unhappy phrenzy stricken mother-loving, “not wisely, but too well,” betrayed-if the chief witness at the inquest be not perjured-into the downward path of sin and shame, and then, ultimately, losing every ray of hope in the dark path on which she had entered, perpetrating the most horrible of all crimes as a fancied means of escape from irretrievable disgrace, degradation, and ruin.

For some months past, a woman of 34 years, named Margaret Sutton, has cohabited with a man of about 32 years of age, named John George Gowland, in a single furnished room on the ground floor, in High Street. They had two children – two pretty girls, were supposed to be married. The dreadful tragedy we are about to narrate dissipated the illusion. His companion, under the heavy burden of mental anxiety, on Sunday night, cut the throats of her two children and her own, and the Gowland, the supposed husband, disowned the impeachment: he declared for the first time that they were not married and that jealousy alone had led the woman – his supposed wife – to destroy herself and her two children. The hope of marriage had been held out to her for several years, but, on various pleas, it was ever deferred. She at length doubted his fidelity, and her paramour returned home on Sunday night, to witness the result of the dreadful tragedy.

Mrs Gowland (for as such she was known) was regarded in the neighbourhood as an amiable, gentle woman, and Gowland’s allegations that she was only his mistress rest upon his unsupported testimony, the truth of which is doubted.

They resided on the ground floor of a cottage, No. 26 High Street, now called Barkerend Road. Gowland returned to the door of his dwelling about ten o’clock on Sunday night. He had left Margaret and his children (according to his own account) in good spirits about six o’clock. His ramble had been long and devious. The house, when he arrived at home, appeared in darkness. He found the door locked. He then rapped, but found no response. He rapped again with the same result, and repeatedly called aloud to “Margaret” to open the door. His rapping was continuous for some time, and attracted the attention of his neighbours by its continuity and loudness. With one of them (Mr. J. Lee), he held some conversation touching the inexplicable circumstance of Margaret’s silence. Wearied with rapping, he ceased to do so, and was content for a time to smoke his pipe quietly as he paced the pavement in front of the house. But he then rapped again, and now he thought he heard some faint stirrings of life within. He still rapped and called out again. There was then a sound of something falling heavily against the door, and then the lock was unturned and the door opened, admitting Gowland into the darkness within. He took a match from his pocket and lighted it, but it went out. He had, however, caught a slight glimpse of the bleeding form of Margaret sitting up in bed. He lighted another match, advanced to the bedside, and then, to his horror, beheld the mother sitting up in the middle of the bed, with her throat cut, and with a dead child, also with its throat cut, lying on each side of her. He rushed from the house in dreadful tremor and called for help. A person called Fawcett, residing on the opposite side of the road, ran to his aid, carrying a light. He no sooner saw the ghastly sight presented than he started from the house to raise the alarm and to give information at the Police Station. The house was soon filled with neighbours, and shortly several police officers, with Mr Grauhan, arrived. Two or three surgeons, including Messrs. Smith, Parkinson, and Terry, were also speedily called in. But the children had apparently been long dead. One was Elizabeth Jane Gowland, aged four, and the other Anne Gowland, aged two years. The medical men immediately applied the necessary means to insure, if possible, the preservation of the life of the poor woman. The scene presented was sickening and horrifying. The necks of the children were dreadfully hacked, and the bed on which they lay as well as the floor were covered with blood. A couple of razors had been used by the wretched mother in effecting the dreadful act. The mother, questioned by some of the persons who went thither, intimated by signs that the deed was a’one hers, and not Gowland’s. She also pointed to a box as if she wished to call her husband’s attention to its contents, and handed to another person a couple of letters. Thought the box was cursorily examined by Gowland at the time, without apparently understanding what the poor woman meant, yet Mr Grauhan and his assistants there found documents, including an order of affiliation in bastardy, which seemed to indicate that she was conscious, from their existence, of what she considered his unfaithfulness towards her and her children.

The poor woman was removed to the Infirmary; an officer being placed in sight of her, as a means of precaution in case she might make another attempt on her own life. When she had been some time at the Infirmary, she appeared to think she would die, and expressed a desire that a minister of religion should be sent for. Mr. Grauhan took immediate steps to that end. Since two o’clock on Monday morning, the Rev. J. Wade, crusts of the Parish Church, has consequently been most devoted in his attention at the bedside of the poor sufferer, offering her the consolations which the gospel can alone give.

The Mayor visited the poor woman at the Infirmary early on Monday morning. Mr Grauhan, the chief constable, and Mr Mitton, clerk to Mr Rowson, accompanied his worship. She was then just able to articulate in a whisper, and again stated that she alone had done the deed, and that her husband was absent at the time. Gowland had been lodged in durance, but he was liberated shortly afterwards.

The poor woman is still in a precarious condition. She is not yet out of danger. If she recovers, she must inevitably be committed for trial for the crime of murder, whatever view may subsequently be taken, as ground for the extension of mercy, of the state of mental aberration under which she no doubt laboured at the time of committing the dreadful deed.

Gowland is an attorney’s clerk. He came to the town nine or ten months ago. He applied for employment to Messrs. Terry and Watson, solicitors. He had recommendations, and received employment. His conduct, so far as it has come under their observation, has been quite unexceptionable. But now, discovering that he has been leading an immoral life, they have dismissed him from their employ. He came from Durham or Sunderland. It has been represented to them that Margaret Sutton was formerly in service at the palace of the Bishop at Durham. The abode of these wretched persons indicated great poverty. It was scantily furnished, and there was one poor bed for the entire family.

The neighbourhood of the dwelling has for several days been thronged with a large and curious crowd, and great excitement has been manifested.

INQUEST

The inquest on view of the body of Elizabeth Jane Gowland was opened on Tuesday, at the Boar’s Head Inn, at half past ten o’clock, before CC. Jewison, Esq., and the following jury:-

Mr. John Hill, foreman Mr. Charles S. Johnson

Mr. John Harland Mr. Samuel Cousen

Mr. J Dawson Sugden Mr. Edward C. Pearson

Mr. Joshua Hainsworth Mr. Geo. H. Farrar

Mr. Thomas Henry Hall Mr. John Carter

Mr. Thomas Hartley Mr. William Jackson

Mr. Henry B. Byles

The Coroner said for convenience the jury would inquire into the death of one child, although the results must be the same in both.

Mr. Grauhan, the chief constable, stated that Gowland refused to attend the inquest unless his expenses were paid and a cab, sent for him.

The Coroner: And do you think he will not come unless that is done?

Mr. Grauhan: I certainly do think so.

The Coroner, after a brief silence, said, I must, then, send a warrant for him, if necessary.

The jury were then sworn, and next proceeded to view the bodies of the children.

On the jury’s return it was reported by Mr Grauhan that the husband was now in attendance.

John George Gowland was then called and sworn. He deposed: I am an attorney’s clerk. I reside in Bradford, Elizabeth Jane Gowland, the deceased, was my daughter. She was four years and six months old. I saw my daughter alive about ten minutes after six on Saturday night last. I saw her in my own house in High Street about that time. Margaret Sutton is the name of the mother of the deceased. She was not my wife. I left her there, and also Elizabeth Jane Gowland and Fanny Gowland, the daughters of the deceased. I returned about ten o’clock the same night. I knocked at the door, but received no answer. I knocked for about five minutes, and received no answer. Mr Joshua Lee, who resides at the next door, then opened his chamber window and said, “Your wife can’t be in.” I replied that it was strange: I never found her out before at that time. I then asked him if he had any idea where she was, and he stated that he had not. I then charged my pipe and began to smoke in the street in front of the house. After smoking for twenty minutes I knocked at the door again. I then heard a slight noise. I immediately began to repeat my knocking. I then heard more noise, and called out “Margaret, Margaret.” I then heard more noise. I repeated my knocking, and cried out in the same manner, being satisfied that there was someone inside; and then I heard a noise as if something was thrown against the door. I again repeated my knocking and called out in the same manner as before “Margaret, honey! Why don’t you open the door?” About a minute afterwards the door was opened and the lock was unturned. I went about two yards within, and, finding all in darkness, I took a match out of my pocket, and lighted it. I then advanced a yard further and saw her sitting upon the bed. The match was finished and I then lighted another match. I then perceived that her throat was cut and the bed clothes all saturated with blood. I also perceived the eldest daughter lying in bed, full dressed, on the right hand side of her, and the youngest on the left side. I then said to her, “Good heavens! Margaret, you have murdered the innocent children!” She made no reply. I then rushed out of the house immediately, and ran across to a neighbour, named Edward Fawcett, who resides opposite. I saw Fawcett, and I said to him, “Oh! Good heavens! Come with me; there is murder in my house,” He then replied and said “Murder!” He then came with me to my house. We both looked in and he immediately ran out. We both looked and found both the children, Elizabeth Jane and Anne Gowland, were dead. Margaret Sutton was sitting up in bed. There seemed to be a deep cut wound in front of the neck of Margaret. Fawcett and I immediately ran out – we rushed out quickly. He used some expression which I don’t recollect. I then called up Mr. Joshua Lee, and shouted “murder.” A great number of people now assembled. We went into the house, and I asked someone to go for a doctor. Two or three doctors immediately came. The chief- constable and several police men came. Prior to the police coming, Margaret Sutton beckoned to me, and I went to her. She then gave me two keys. She motioned to a box. I opened the large box to which she pointed. Some person stated that very likely there would be a written paper found in the box which would state why the deed had been done. I replied that it could not be, because she could neither read nor write. I did not find any writing in the box. I took 8s out of the box, and I believe I then locked it. This was all the money I saw. I did not look a minute there. I was then told she wanted me, and I went to the bed side and said “There is no writing,” and she then took two letters from her pocket. The first letter I saw was directed by myself to her brother at Hylton, and the second though was one received from him.

The letters were produced by Inspector Shuttleworth, and the Coroner read on, as follows:-

Hylton. Oct. 19

Dear Maggie,

In reply to your letter, I am very sorry to hear of the situation you are placed in, but you have no one to blame but yourself, as I and your sister Ann advised you not to go with him, but it was all to no use – you would have your own way. I thought you had plenty of him before, when you left him twice, and went to him again. Mrs Laing said she tried all she could to keep you away from him, but it was all of no avail, and she will never look to you again. Mrs Laing met your mother at Sunderland and asked her if you had got a situation. I, herself, and Mr. Jas Laing signed our names to you and Gowland. She was very anxious to know, and I wrote to Gowland and I enclose his reply, for I do not think you know anything about it.

Dear Maggie,

I think you had better stay with your husband and not leave him a third time. You know sister Mary is not here to mind the children now. You will only set people on to talking about you again. If you cannot live with him, you can get law to make him keep you and the children. I remain, your affectionate brother,

WM. RICHARDSON

Witness continued: Someone then said, “Who has done the deed?” and she put up her hand, and motioned towards herself. I believe she could not speak. I had had no reason to think she would do anything to herself. She was a nice gentle creature. About a fortnight ago, she intimated to me that she would like to be married. I replied that I would be married before the year was ended, and I told her further that it would have been done in the North of England, but we were afraid of its being known there. I received letters morning after morning from various parts, and she seemed to scrutinise the letters very much. One morning, about ten or twelve days ago, I asked what were her reasons for examining the letters so closely, and she replied. “Well, you know, Gowland, I have a good right to be jealous of you.” I then asked her why, and she replied, “Have I not been told you have been seen talking to women?” I then told her that as a person in my capacity of life, as a law clerk, I was bound to do so in the way of giving advice on behalf of my governors. She occasionally asked me who the letters were from, and I told her on every occasion. I also tendered the letters to her and told her she might take them to a neighbour and get them read. Some of the letters were from my friends, others from her friends, and others from my employer’s clients. I generally left some of the letters in the drawer, and answered them in the evening. She could never yet find a letter I received from any woman.

Mr Grauhan here suggested the inquiry whether the witness had not been seen in a brothel recently.

The witness, after some hesitation and equivocation said: About a fortnight ago I went to a house of ill fame opposite to speak as to its being an improper house, and to tell them I should lodge a complaint against them to the magistrates for keeping an improper house. I paid for some oysters. Margaret came in at the time and said, “What are you doing here?” and I said, “Well come along with me, and I will tell you.” I told her what I had been stating to the parties – that I had been threatening them with proceedings. I did not tell her that I had been treating anybody with oysters. I treated nobody in particular, but I was ready to treat anybody. The man’s wife asked me to stand treat, and I treated everybody around. I did not treat any person in the house in particular. I can’t say whether I told Margaret that. They did not turn me out, but I came with her. When I told her what occurred she appeared satisfied, and we have not had a word since I explained. I am under the impression she has been jealous of late. She was perfectly satisfied with what I told her at the time. She has always been kind. I deny that we have been parted twice; we have been parted only once. I believe this dreadful affair has been the result of jealousy, and that feeling may have affected her mind. (The witness modified this statement.) On Sunday morning, after breakfast, I told Margaret I was going out, and she would have to have the dinner ready at one o’clock. I did not return till half past two o’clock, and she observed “Is this at one o’clock, John? “Where have you been?” I told her I had been up Bolton Road and then went to Shipley. On-going along the fields, I overtook some women, and asked them the road to Shipley. I called to see a Mrs. Crabtree, whose husband is in York Castle and said I had staid ten minutes of a quarter of an hour with her and her family, and the woman had invited me to dine, but I declined. Nothing further was said. I think it was satisfactory. I got my dinner at home. Margaret, the children, and myself had tea together on Sunday afternoon. We were very friendly indeed. I can’t give any opinion as to why the deed was done, further than I believe she was jealous. On leaving after tea I went into the town, and then two miles on Bolton Road, then on Manningham Lane, and then went to Mrs. Jackson’s, in Green Lane, and then came back home. I have been out sometimes till ten o’clock. I have perchance been out till twelve o’clock, and some weeks ago I was at supper-

The Coroner: We are not going into the history of your life; if we were to do that it would be endless.

Some of the jury were of opinion that the inquiry would throw light upon many “flying reports.”

The Coroner said that Margaret Sutton was not justified in doing any such deed in consequence of any act of the witness. He did not think any suspicion could arise to implicate any other person. The jury could have no doubt but the woman had committed this deed. Whatever might be his misconduct, this did not make him responsible for the crime. No doubt he might be severely blamed by the public, and properly so, but he was, he said, ready to answer any question, and the jury could now put any question they chose.

Several of the jury continued to put questions, and the witness stated that he received a pound a week from his employers, but he received money besides, and he never allowed Margaret less than 18s per week.

Joshua Lee was then called. He said: I live in Barkerend Road. About a quarter past ten, Gowland came knocking at the door. I was in bed. He tapped at the door and called repeatedly “Margaret.” I came to the door, but ran in. I had heard him knocking at the door for some time. My wife went in and came out again. My wife said that Margaret had cut the children’s throats and her own. I did not go in, and have not seen them. There was unpleasantness going on every day in the house. His wife has repeatedly told my wife that he was very distant and did not speak to her. I did see Gowland go into the bad house opposite. There were two men. They shut the door after them. Gowland has come in at all times of the night.

A conversation again arose as to the putting of what the Coroner said were irrelevant questions touching the conduct of Gowland, insisting that the jury’s only province was to ascertain who had committed the crime.

Edward Fawcett, being called and sworn, said: I reside in Barkerend Road. About 20 minutes to 11 on Sunday John George Gowland came to my house, threw the door open, and said he wanted me. I asked what was the matter, and he said “”Come along.” All was in darkness. There was no light in the house. He said “My wife has cut her own throat, and murdered both children!” I told him to get a light. He did so. I then saw the woman and both the children in bed with their throats cut. The wife was sat between both children on the bed. Her throat was bleeding. The children had their clothes on. I did not speak to the wife. Nothing was said in my hearing between Gowland and his wife. I don’t know anything about the manner in which these people have lived together. She seemed a very close, nice woman. I heard some knocking at the door before I was called. This was about teen minutes before Gowland came for me. When I went to the house, I asked Margaret Sutton if Gowland had done it, and she made motions saying that he had not; she had done it herself. The key was inside the door.

Ruth Gell was then called and sworn. She said: My husband is Alfred Gell and he is a leather currier. As I was going from my own door, on Sunday night, Edward Fawcett was running down the street, greatly alarmed. I was going from my own door into the house. I heard a knocking, and was told there was something to do in Gowland’s and went in. I went to the bedside and saw Mrs. Gowland herself and two children had all their throats cut. I said, “Mrs. Gowland, who has done this?” and she put her hand out and pointed to a bloody razor on the bed, and then pointed to her bosom. She did not speak, but only motioned so as to make me understand it was her. I then said, “Who opened him the door?” and she pointed to herself. She was quite sensible. She took out two letters from her pocket, gave them to me, and then laid a penny upon one of them, and pointed as if she wished me to post it. I gave the letters to Mr. Shuttleworth. She also gave me a key for the box. I have been there sometimes.”

(Several MS. Pieces of love-rhyme found in the box were here presented by the chief constable. The poetry was believed to be in the handwriting of Gowland.)

In answer to inquiries of a juror, the witness said that the meals of the family were very scanty, and she thought they had not sufficient to eat. Mrs. Gowland did not tell her so, but she got this impression.

George Priestley Smith, surgeon, High Street, was then sworn. He said: I was sent for to see Mrs. Gowland and her two children about half-past ten on Sunday night. I was not aware till now that her name is Margaret Sutton, and not Margaret Gowland. I went to her house and found her sitting on the bed with her throat cut, and her children with their throats cut at the head of the bed. The skin, muscles and windpipe were all cut through and divided; the artery and jugular vein were not injured. The bleeding had completely ceased when I got there, at near eleven o’clock. Her face and arms were covered with blood. She was quite conscious, but whispered very indistinctly. The two children were lying quite dead, behind her, at the head of the bed. They were both on their right sides with their throats cut. She made a motion as if she wanted to say something to me, and she motioned as if she wished me to understand she had done it herself. This razor I found behind her upon the bed. The wounds in the throats of the children were deep wounds, which divided the carotid arteries, jugular veins, the trachea, and oesophagus. The appearance of both the children and the mother was blanch less. I have no doubt that the death was caused by these wounds in the throat.

Some conversation arose as to the expediency or otherwise of having a post mortem examination, and the Coroner said that he would leave the point to the decision of the jury, but explained that, it would be much better to have such inquiry test any technical difficulty might arise in any further investigation elsewhere.

Mr. Grauhan stated that, amongst the papers found in the box was an affiliation order on Gowland for a bastard child, and that it was quite possible, some person might have read her this paper as well as the poetry.

The Coroner then suggested that a post mortem examination had better be made, observing that in that case an adjournment of the inquiry would be needed, so that the probability was they might, at the next meeting, have an opportunity of seeing the poor woman at the Infirmary.

He would not of course recommend that the question should be put to her; but the jury might give her the opportunity, if she thought proper, of course after due caution, of giving an answer to the charge which was made against her. The jury no doubt might be disposed to think that this dreadful deed was done in a moment of mental aberration, caused by the severe agony of feeling under which she might have been for some time suffering. That might be so, but the jury had really nothing whatever to do with the question. That could not make the slightest difference in their verdict, because, if the evidence went to show that she was guilty of this crime, it would be their duty to find her guilty; leaving it to a higher court to decide whether, under the circumstances, the poor woman was responsible for the act at the time.

The jury appeared to concur in the suggestion as to an adjournment in order to obtain a post mortem examination of one of the children, Elizabeth Jane Gowland; and the Coroner accordingly took their recognisances to appear before him on Tuesday, 6th proximo.

The jury then separated, and as they did so, Gowland came to complain of the hardship and inconvenience of an adjournment, provided he would be required to attend. While expressing great affection for Margaret Sutton, he said he could find no peace in the town, and he was wishful to leave it as soon as possible. The Coroner immediately bound him in his own recognizance to appear on the 6th of November.

GOWLAND RE-APPREHENDED

SUSPECTED PERJURY OR FORGERY

Shortly after the inquest, on Tuesday afternoon, Gowland was apprehended again and placed in the lock-up. Amongst the papers found in a box at his dwelling was a paper which purported to be a copy of the register of the marriage of John George Gowland with Margaret Sutton, at the parish church of St. Oswald, in Durham, on the 23rd of September, 1855. The following is a copy of the document:-

Other papers of a grossly obscene character, were also found on the person of Gowland.

Yesterday morning, the prisoner Gowland was brought up at the Borough Court, before Mr> Alderman Brown and Mr. Alderman Rand. A large crowd of persons followed the prisoner as he passed through the streets to and from his cell.

On Gowland being called into the dock,

Mr. Grauhan, the chief-constable, stated that he held in his hand a document which purported to be a copy of the register of the marriage of John George Gowland to Margaret Sutton, at the parish church of St. Oswald, in or near the city of Durham. This document indicated that the prisoner had been guilty of either perjury of forgery. He (the prisoner) was present as a witness at the inquest held on his two children on Tuesday, and he there swore that he was not married to Margaret Sutton, who had lived with him as his wife, and who was now in the infirmary. Reading the paper which purported to be a copy of the register of the marriage between Gowland and Margaret Sutton, Mr. Grauhan stated that this document had been found amongst other papers in the possession of the prisoner. He (Mr. Grauhan) had already written to the incumbent of St. Oswald, in Durham, and he now asked the bench to remand the prisoner till Monday next. He thought he should be able to show that the prisoner had made use of this document while in Bradford, and that, if he were not guilty of perjury he was guilty of forgery. He had to ask that the prisoner be remanded till Monday.

Mr. Alderman Brown ordered the prisoner to be remanded till Monday.

The prisoner was sent into the dock, as he was about to speak. It was discovered that he wanted to make application to offer bail.

Mr. Grauhan said he objected to the application. He had certain grounds for believing that the prisoner was a most immoral character, and that, if he were bailed out, in all probability the bench would never see him again. He had already documentary and other evidence to show his character.

The application being refused,

The prisoner then asked if, he might be allowed to write to his mother and also to friends to obtain the means to get something to eat while in prison.

Mr. Grauhan said that, while the prisoner was in custody, he would have to fare as other prisoners, he would have prison diet, and if he wrote to his mother or any other person, he (Mr. Grauhan) would have to see it.

Mr. Alderman Brown said that this must be the case; if he wrote the chief constable must see the letter.

The prisoner was then removed to the Police Station, followed by a large crowd.

The prisoner’s demeanour indicates apparently the most callous indifference as to his present position and the melancholy circumstances of his family.

On Tuesday afternoon, while at the infirmary, Mr. Chief Constable Grauhan asked the poor woman whether or not she was married to Gowland, and she replied that she was not. This admission seems to support the declaration of Gowland. Still, there are circumstances that which go to support the belief that they were married. It is said that the Vicar has received a letter from a clergyman, in which they are spoken of as married persons. The letter of Wm. Richardson, read at the inquest, also goes to confirm this impression. And some nine or ten months ago, Gowland, on coming to the town lodged for eight weeks at the house of Mrs. Campbell, in Park-gate. For about six weeks, Gowland represented himself as a single man. He then told her he was not single but married, showing to her what appeared to be his “marriage lines.” He said he had a wife and two children, and had taken a house for them in Barkerend Road. Mrs Gowland arrived with her children in about a fortnight after, and has since that time been living with Gowland at the cottage hired by him.

MISCELLANEOUS

After the inquest, Mr. Grauhan, at the suggestion of the Coroner, visited the poor woman at the Infirmary, his object being, in case the medical officers would permit, formally to charge her with the crime of murdering her two children. Several medical officers would permit, formally to charge her with the crime of murdering her two children. Several medical gentlemen were present and were of opinion that the charge might be made without prejudice to her condition. This was accordingly done – Mr. Grauhan giving her the usual caution that she need not say anything unless she chose, and that, if she did say anything, it would be taken down and might be used as evidence against her elsewhere. The poor woman maintained a perfect silence – she offered no reply.

Yesterday morning, a sister of the poor woman came to see her, but she had no sooner got a glance at the face of the poor sufferer than she fainted and fell, and had to be removed to a bed in an adjourning ward in the Infirmary.

Yesterday afternoon, the funeral of the children took place at the Borough Cemetery. The funeral procession at the rear of the hearse was composed of little children who had been the playmates of the deceased. The night was a novel one as it moved through the crowded streets. A large crowd of spectators followed. At the grave, the funeral service was read in a solemn and impressive manner by the Rev. W. Mundy, curate of Great Horton. The crowd assembled in the Cemetery grounds was very large. Many women were in tears.

On inquiring at the Infirmary at a late hour last night as to the state of the poor woman, the answer returned was – “Very bad-she gets worse; there is little, if any, hope of her recovery.”

The Bradford Observer, November 1, 1860

THE MURDER OF TWO CHILDREN

On Thursday last, Mr. Grauhan, the chief constable, received a letter from the Rev. Edward Sneyd, vicar of St. Oswald, Durham, in which the rev. Gentleman stated that he carefully searched the register of marriage in the parish of St. Oswald, for the year 1855, and found no entry of the solemnization of any marriage between John George Gowland and Margaret Sutton during that year. He added that there could be no doubt that the certificate described was a forgery. In answer to another letter then written by Mr. Grauhan, the vicar of St. Oswald replied that to the best of his knowledge and belief, there neither was nor had there been during his incumbency any clergyman of the name of Henry Thomas Fox, resident in the parish of St. Oswald. The certificate of the entry sent him, he added, was not worded in the form uniformly adopted by him or his officials.

Mr. Grauhan also received by the same post a letter from the brother of Margaret Sutton – Mr. Richardson, of Hylton, Durham, in which the enclosed copies of two letters, which he stated he had received from his sister. They were as follow:-

Dear Brother,

With heartfelt grief I write these few lines to you to inform you of the situation I am now placed in. I am not in a house of my own at present, not am I likely to be, the way as my husband is going on-the same as he was in Sunderland, if anything worse. I really cannot bear it any longer. Dear Brother, if I am spared till Monday, I intend to leave him, so that you may expect me by that time, if I can get sufficient money of him on the Saturday to bring me and the children home unknown to him, as he will not let me come if he knows. Please not to say anything about it till you see me, perhaps he might get to know. I shall come by the Great Northern (North Eastern) but it will not be until night; so you will be there to meet me. Dear Brother, in haste, from me,

Your unhappy sister,

MARGARET GOWLAND, Bradford

Please write to me by Sunday, and send it in the envelope directed for Mrs. Hutchinson; then he will not know about it, and I will get the letter forwarded to me Good bye.

Bradford, Oct. 21

Dear Brother,

Let the consequences be as it may, I shall leave Gowland tomorrow, Monday, I cannot put up with his treatment of me any longer. So you may expect to me to come tomorrow night by the last train to Aylton.

MARGARET GOWLAND

The brother still wrote under the impression that Gowland and his sister are married – he says that “it is too true, they are married.” He stated that they had been parted twice. He spoke of Gowland as having been the source of all family trouble and sorrow for many years past. He was capable, he alleged, of committing any kind of iniquity. Amongst other offences, of which he had been guilty, was that of felony, for which he had been imprisoned six months in the Durham gaol. The brother went to the railway station in vain. He stated that he would be present at the adjourned inquest.

GOWLAND LIBERATED

On Monday, John George Gowland was brought up at the Borough Court; the magistrates present being the Mayor (Isaac Wright, Esq.), W. B. Addison, Esq., John Hollings, Esq., Wm. Rand, Esq., Mr. Alderman Light, and Mr. Alderman Brown. The court was densely crowded with spectators. The passages leading to the court, and also the streets outside, were crowded with people anxious to obtain a sight of the prisoner.

The prisoner was placed in the dock. He appeared much agitated. He asked the bench to be supplied, before the case commenced, with paper and pencil, and these were accordingly supplied to him.

Mr. Grauhan, the chief constable, stated that the prisoner was remanded last Wednesday. The reason of that was that at the inquest on his children he deposed that he was not married to the woman who gave her name as Margaret Gowland, and who was now in the Infirmary. He (Mr. Grauhan) wrote to the Rev. Edward Sneyd, the vicar of St. Oswald, Durham, to ascertain whether such persons had ever been married at St. Oswald parish in 1855, a document purporting to be a certified copy of the prisoner’s marriage with the woman having been found amongst his papers. The Rev. E. Sneyd wrote to say that he could not find that any such marriage had taken place. The name of the clergyman purporting to have signed the supposed certificate was Henry Thomas Fox. There was no clergyman there of that name, but there was a clergyman named George Townsend Fox. This certificate is in the handwriting of the prisoner, and I can prove that he used it, but I cannot prove that he used it for a fraudulent purpose. The charge of perjury, therefore, cannot be sustained, nor can the charge of forgery.

Mr. Alderman Brown: Will you state in what respect the document has been used?

Mr. Grauhan: When the prisoner first came to the town he showed this document to the woman at whose house he lodged. He first said that he was a single man, and then that he was married and had two children. At that time, he showed his certificate and said he was married.

Mr. Alderman Brown: Have you no instance in which this document has been used.

The Mayor: It has been used; but not on any fraudulent pretence.

Mr. Grauhan: That is the case; not on any fraudulent pretence. He has used this document, but not for any fraudulent purpose.

The Mayor (to the prisoner): Have you any question to put to the witness?

Gowland: Yes; may I ask to be allowed to look at the document that has been put in? (The paper was handed to him.) You have seen this Mr. Grauhan; and you say there is no person named Henry Thomas Fox? Have you written to Durham?

Mr. Grauhan: I have, and I am told there is no such person.

Gowland: Will you let me see the letter of Mr. Sneyd?

Mr. Grauhan: No; there is no such person as Henry Thomas Fox.

Gowland requested that any witness who were about to be called might be sent out of court.

Mr. Grauhan replied that there was no necessity for anything of the kind, for he had no witnesses to call.

Gowland: Have you no witnesses to call to prove the signature of Henry Thomas Fox?

Mr. Grauhan: I would have brought witnesses, if I had thought it necessary to do so, but I have not done so.

Gowland: There is Elizabeth Proud? Have you got her here today?

Mr. Grauhan: I have not; if I had thought it necessary I should have done so.

Gowland: Have you got Henry Wilkinson here?

Mr. Grauhan: No.

Gowland: What parties have you applied to?

Mr Grauhan: None. I did not think it necessary to do so.

Gowland: Have you written to parties at Durham for the purpose of obtaining information?

Mr. Grauhan: I have written to one.

Gowland: What parties have you written to besides those spoken of (no answer was returned). I submit this question is a proper one, and ask if I have not a right to an answer to it?

Mr. Grauhan: I have no right to disclose anything I may know, or any information I may possess.

The question was again put, and the bench thought Mr. Grauhan need not answer such a question. Gowland then asked if he could have a sight of the letter received from Mr. Sneyd; but Mr. Grauhan declined to hand it to him.

Gowland put the request again, and the Mayor said that such a request could not be yielded. The magistrates consulted for a few minutes, and the Mayor said that the prisoner was discharged.

The object of these questions could not be determined, and they must have been put in entire ignorance of what Mr. Grauhan had stated.

In a short time after Mr. Superintendent Milnes removed Gowland to the area below the Court House, but as it was not safe for him to depart from the Court House, he remained there for five hours. A large crowd still remained there, and it was at last deemed expedient by the officers to assist him to escape over the high wall in the rear of the Court House. Thus climbing the wall into Drake Street, he got into a cab near the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway Station, and ordered the cabman to drive him to No. 26, Green Lane, Manningham.

GOWLAND IN COURT AGAIN

Yesterday, Gowland came before the Borough Magistrates and applied to them to make an order on Mr. Grauhan, the chief constable, to give up to him property belonging to himself, which the officer had in his possession. He stated that Mr. Grauhan had 20s. Belonging to him.

The Mayor replied that the bench had no power to interfere in the matter.

Mr. Grauhan said that he held 20s. Belonging to the woman, who was at the Infirmary, and she stated it was her money.

Inspector Shuttleworth said that there were only two old coats belonging to Gowland. Gowland (who held some letters in his hand) then said that the papers had said a good deal as to “manufactured characters” (testimonials), but he would beg the bench to look over the papers he held in his hand.

The Mayor replied that the bench declined to look at the papers.

Mr. Grauhan said that what property he held he should retain till after the inquest, but he had nothing but what he believed belonged to the woman, and it consisted of the money he had mentioned and some clothing. The fellow, whose appearance was sudden and unexpected, then disappeared.

MISCELLANEOUS

The poor woman still continues in a precarious condition, sometimes better, sometimes worse, and the medical officers are somewhat divided in opinion as to the reality. She is very weak. She appears to be gradually sinking. She was very bad on Tuesday, and was worse yesterday. A lapse of two or three days will remove any doubt that may remain as a result.

We find, from private letters and newspapers received from Sunderland and Durham, that the dreadful tragedy has created great sensation also in that part of the country, and feeling of deep commiseration for the poor woman.

(From the Durham Advertiser)

Gowland is a native of Durham, his father and mother having for many years kept the “Seven Stars” public-house in Claypath. He was formerly a clerk with Mr. H. Marshall, solicitor, in this city; but on being discharged about five years ago he went to Sunderland, and some time afterwards contrived to elope with the wife of a seaman named John Cuthbertson Bellas, whilst he (Bellas) was at sea. Having taken with them the whole of the unfortunate man’s furniture, Bellas, on his return home, had Gowland apprehended on a charge of stealing his property, for which he was committed by the magistrates to Durham Gaol, and eventually, at his trial at the Easter Sessions, 1859, was sentenced to six months imprisonment with hard labour.

(From the Durham Chronicle)

The prisoner Gowland is a native of Durham, his mother and other relatives now living in the town. The case has consequently excited a great deal of attention here; and sincere sympathy is expressed for the unfortunate woman he had induced to become his victim, and who, when heartbroken by his cruelty, dared to take the lives of her children and of herself. Gowland himself is a well known person, as he was somewhat of “a character.” He was formerly an attorney’s clerk in the employment of Mr. Henry John Marshall, in this city, and was afterwards similarly employed in Sunderland. He is a vulgar, impudent, conceited fellow and it is somewhat surprising the influence he seems to have acquired over some of his female acquaintances. He was committed to Durham prison by the Sunderland bench, of magistrates, on the 23rd March last, on a charge of stealing household goods, the property of John Cuthbertson Bellas, at Sunderland. He had been living in adultery with Mrs. Bellas at lodgings, whilst the prosecutor, a sailor, was at sea, and for this offence he was sentenced by the Court of Quarter Sessions to six months’ imprisonment. He also appeared before the magistrates at the Newcastle police court for assaulting a woman whom he had taken to his lodgings, by pitching her out of the window. He was not married to Margaret Sutton, and the pretended marriage certificate is fictitious. The Rev. George Townsend Fox was curate at St. Oswald’s Church, but no ‘Henry Thomas Fox’ has occupied his position, so that the charge of forgery will, it is feared, fall through.

Gowland and the unfortunate woman had been once or twice parted, she going to her friends at Hylton. After he left Durham gaol she again agreed to live with him, and they went to Bradford. His testimonials, if examined, will probably prove to be of “home manufacture.” Whilst at Sunderland he induced a number of silly people to subscribe one shilling a week each to him for the purpose, as he induced them to believe, of carrying on proceedings for the recovery of some landed estates in this neighbourhood, to which he pretended he had a title. This swindle would have probably been exposed at the time, but it happened that he was sent to gaol from Sunderland before the poor people discovered they were being duped.

The Bradford Observer, November 8, 1860

THE RECENT TRAGEDY IN HIGH STREET

DEATH OF MRS. GOWLAND

At a few minutes past six o’clock on Friday morning, Margaret Gowland alias Sutton died in the Infirmary. Her demise, as we stated in our last, was imminent, and from Thursday evening she gradually sank. The highest medical skill and the most unremitting attention and kindness were exerted in vain. Up to Thursday, she was apparently frequently disturbed by severe mental agony. She frequently talked of her children and uttered the wish that she were with them! On Thursday she appeared to find consolation in listening to the reading of portions of Scripture in which there was the promise of forgiveness to the penitent in heart, and when the reader ceased, she desired to read the passages again. In the evening she became more calm and quiet. About one oclock on Friday morning she remarked that “she was now reconciled,” and “she hoped god would forgive her.” From that time, though sensible nearly to the close of her life, she sank rather rapidly, and at length she passed peacefully away.

INQUEST

The inquest on Margaret Gowland alias Sutton, who died in the Infirmary, on Friday morning, was held on Saturday, at the Boar’s Head Hotel, before Mr. C. Jewison, Coroner and the jury previously empanelled to inquire into the death of the children.

Gowland, who had been summoned as a witness, was, on his own application, allowed to be in court.

Frederick William Grauhan, chief constable, was the first witness called. He said: I am the chief constable of Bradford. On Sunday, the 21st October, about a quarter to eleven o’clock at night, from information I received, I went to the house of John George Gowland, in Barkerend Road, and there found the deceased, who had her throat cut. She was sitting up on the bed fully dressed, and the children on each side of her, with their throats cut, and quite dead. I sent for a cab and sent her to the Infirmary. I had no conversation with her then, but I saw her next morning in company with the Mayor, and Mr. Mitton, clerk to Mr. Rawson, clerk to the borough justices. She was asked whether John George Gowland had murdered the children. She said, “He was not in at the time and knew nothing of it.” She said – “I did it.” These questions were not put by me, but in my presence.

Edward Fawcett was next called. He said: I saw Margaret Sutton on the 21st October. Gowland came to my house about twenty minutes before eleven o’clock. He said, “Come on, I want you.” I asked him what was the matter, and he said “Come on, come on!” I then followed him into his own house, which was opposite. There was no light and no fire. I said again “What is the matter?” and he said, “I believe my wife has murdered both the children and cut her own throat.” He then struck a light. I saw the children on the bed. They had their throats cut, and Margaret Sutton was sitting between them. The children were quite dead, and she was bleeding from a wounded throat. I went to the police station and told what had happened, and returned back again as quickly as I could. I returned back to Gowland’s. I asked her when I got in whether Gowland had done it. She made motions to signify she had done it herself. She pointed to a bloody razor lying on the bed and then to the children. She also pointed to herself and shook her head. I had heard a knocking at a door before Gowland came to me. I make no doubt that it was her own act. There was no light in the house. I observed the key was inside the door. She appeared to be quite sensible at this time.

Mary Brook was then called. She deposed: I reside at 22, High Street, and live next door to John George Gowland. I was acquainted with Margaret Sutton. I knew her for two or three months. She was a quiet, respectable woman. I did not know but she was married. She has been in our house sometimes three or four times a day. She regretted her connection with Gowland very much and very often, and in talking about it she frequently got excited. She had never been so bad as after Gowland had been in the house of ill fame opposite. This was about a fortnight before. She got worse during the last fortnight. She came into our house the morning after, and said she could not bear it, and it would send her to the grave. She said, “Oh, Mrs. Brook, this will kill me.” On the Saturday night previous to the event, she looked very melancholy. She looked very wild and low, and I said, “Keep up your spirits.” She appeared to dread Sunday coming. I knew she was going to leave Gowland on the Sunday night about seven o’clock. She came to bid some people good bye. She appeared about the same as on Saturday. She had sent a letter on the Sunday to her brother at Hylton, telling her to meet her at the Hylton station on Monday. She used to speak of Gowland’s ill using her-drinking and staying out at night. He came home sooner than usual on Saturday night, the 20th, and she was afraid from that circumstance he suspected her going off. He gave her 12s. 6d. that night, which was more than usual. He gave her 6s. 6d. the week before.

George Grauhan was then sworn. He said: I am the house surgeon at the Bradford Infirmary. The deceased was admitted into the Infirmary on the 21st of October, at twenty minutes to twelve o’clock at night. I found her suffering from a severe wound in her throat. The windpipe was laid open, but the large vessels were not injured. I attended to her immediately. She was also attended by other surgeons. A police officer was place in charge of her to prevent her doing herself any further injury. The officer asked her if she had done the injury herself, and she nodded assent. She gave me to understand several times that she had done it herself. Her mind did not appear to be affected, except that she was dejected at times and in low spirits. She appeared to be in a sound state of mind until the latter end of her existence. She expressed a desire not to get better. She died from the indirect effects of the wound.

By a juror: I cannot say whether the great loss of blood might have had any effect in the inducing the return of sanity after the infliction of the wound.

The Coroner observed that he thought the evidence given might conclude the inquiry. The evidence was very clear, and any further evidence would be unnecessary.

Mr G. H. Farrar asked whether there was any more evidence as to the state of the woman’s mind.

The Coroner replied that he thought the evidence as to her state of mind at the time she cut her throat was very clear indeed. If, however, they wished to have more evidence they might perhaps get it. Mr. S. Cousen suggested that they adjourn the inquiry till Tuesday.

The Coroner replied that he could not see the object of an adjournment. They did not doubt that the woman had cut her own throat?

Mr. S. Cousen: No.

The Coroner said that the only question on which they needed to be satisfied was as to the state of her mind at the time she did the act.

The Coroner said that upon that point he thought the evidence was quite sufficient and conclusive. The jury were aware that Gowland, who was examined at the first enquiry, stated that he left the woman at six o’clock.

Gowland: Ten minutes past six, sir.

The Coroner ordered Gowland not to interfere. At that time the woman, he said, was quite well and cheerful; but then they had the evidence of a person who saw her at her house at seven o’clock, and she described her as being then in a low and unhappy state of mind. That unhappy state of mind was not to be wondered at. Her mind had unquestionably been distracted in consequence of the degraded state in which she had been, living and cohabiting with Gowland, they being unmarried; and it appeared very clear, from the evidence before them, that she had been pressing him to marry her, and that, in order to quieten her importunities, he told her he would marry her before the close of the year. It appeared that she had no faith in that promise; probably she had had many promises of that kind before. At no time did she believe him, because she had been driven to write to her brother to tell him to meet her at the Hylton station, having finally made up her mind to leave him on the following Monday. From one of the letters which the jury had seen, it appeared that her brother wrote her a letter to advise her to remain where she was, and he stated that her sister had again gone out to place, and that therefore there would be nobody to look after the children. She knew very well that, if she went home, there would have been a stain upon her reputation, and the probability was that the children would have been a great clog not only to herself but upon her friends, and that this poor creature saw nothing but trouble before her, whether she went home or stayed with Gowland in Bradford. It was just possible that, reflecting upon her condition, her mind became frenzied and deranged, and that she might have done this serious mischief during the time she was in that state. As a juror had suggested, it was probable that the loss of blood from the wound in her throat might have had some effect in restoring her to consciousness, because the jury had been told that she was quite conscious after ten o’clock, when Gowland came home, and some of the neighbours went into the house with him. If the jury had any doubt as to the state of her mind when she committed the deed, they could leave the matter in doubt. If they found that she was in a sane state of mind at the time she committed the act, then they would refuse her the rites of Christian sepulchre.

The room was then cleared of strangers, and in a few minutes the jury agreed to return the following verdict:-

“That the deceased, Margaret Sutton, died from the effects of a wound on her throat, inflicted by herself with a razor, she being at the time in a state of temporary derangement of mind.”

Gowland, hearing the verdict, shortly after the coroner’s constable, who had communicated it to him that he was very glad such a verdict had been given.

The remains of Margaret Sutton were interred at the Borough Cemetery on Monday afternoon; Inspector and Constable Sharp undertaking the arrangements) as in the case of burial of the children) for conducting the funeral. Three cabs, in which were a sister of the deceased and a number of neighbours, attired in mourning, followed the hearse as it departed from the Infirmary grounds, soon after two o’clock. A large concourse of persons, principally women, had gathered in the adjoining streets, and they followed the funeral procession as it departed. The crowd increased as the procession, attracting general notice, moved forward, and when it had reached the cemetery grounds at Scholemoor, it was very large – two or three thousand in number. The Rev. J. Wade, the curate of the parish church was the officiating clergyman; unremitting in his attention to the deceased in the last days of her life, he performed the last sad office over her grave, reading the sublime and touching burial service of the Church of England with great solemnity and effect.

The grave was situated near the western boundary. The coffin was deposited in the grave, and the coffins and remains of the children – were afterwards placed in the same grave. They had been removed from a grave in another part of the cemetery. The bottom of the grave was built round with bricks and covered in with flags.

It appears that at the close of the inquest on Saturday a subscription was commenced in aid of an effort to procure for the mother and children a superior grave than they otherwise would have had to erect, a memorial over the grave, and a considerable sum of money (£20 or £25) was obtained for this purpose in two or three days, almost without solicitation.

Margaret Sutton left written directions as to the manner in which Mr. Grauhan, the chief constable, should dispose of such property as she leaves behind, which includes 20s., a quantity of wearing apparel, a Bible, and a wedding ring. Her mother, Elizabeth Sutton, of South Hylton, Sunderland; a younger sister, also residing at Sunderland; and a sister of Gowland (a Mrs. Dixon, residing at Undercliffe Cemetery lodge), are the legatees. Very curiously, the poor woman bequeaths to Gowland’s married sister the wedding ring she wore, though, as it now appears, she was unmarried, and to her husband her Bible. They are said to have always been kind and affectionate towards her, and, to have sympathised with her greatly in her domestic sorrows and troubles.

ADJOURNED INQUEST ON THE CHILDREN

The adjourned inquest on the children was held on Tuesday at the Boar’s Head. On the jury being sworn, the Coroner observed that it would now be unnecessary to take up the time of the jury in taking down the evidence of the medical gentleman with respect to the post mortem examination; though, if the unfortunate woman had lived, his testimony would have been of the greatest importance.

Mr. Parkinson, surgeon, was then sworn, and he stated: On the 23rd October I made a post mortem examination of the deceased, Elizabeth Jane Gowland, assisted by Mr. Smith and Mr. Terry. Externally there was a wound across the throat, four inches in length, dividing the windpipe, the gullet, and the large vessels. I examined all the internal organs, and found them quite healthy. In the stomach there was a quantity of partly-digested food. This remark may answer the question raised that the children had had no food. I am of opinion that the child died from haemorrhage caused by the wound in the throat.

The Coroner: The circumstances are so clear, that it would be an insult to your understandings to ask if you wanted any further evidence. Then consider your verdict. I think we need not withdraw for the purpose. Do you find that the deceased Elizabeth Jane Gowland was killed or murdered by her mother Margaret Sutton, and that she did this at a time when she was labouring under temporary insanity of mind?

The jury expressed their acquiescence in the verdict, and it was accordingly entered upon the inquisition, and duly signed by the Coroner and each juror.